About Us

Our Portfolio

Investors

Sustainability

Media

By Hugh Moorhead

There’s a revival going on in retail real estate – here’s how investors can take advantage.

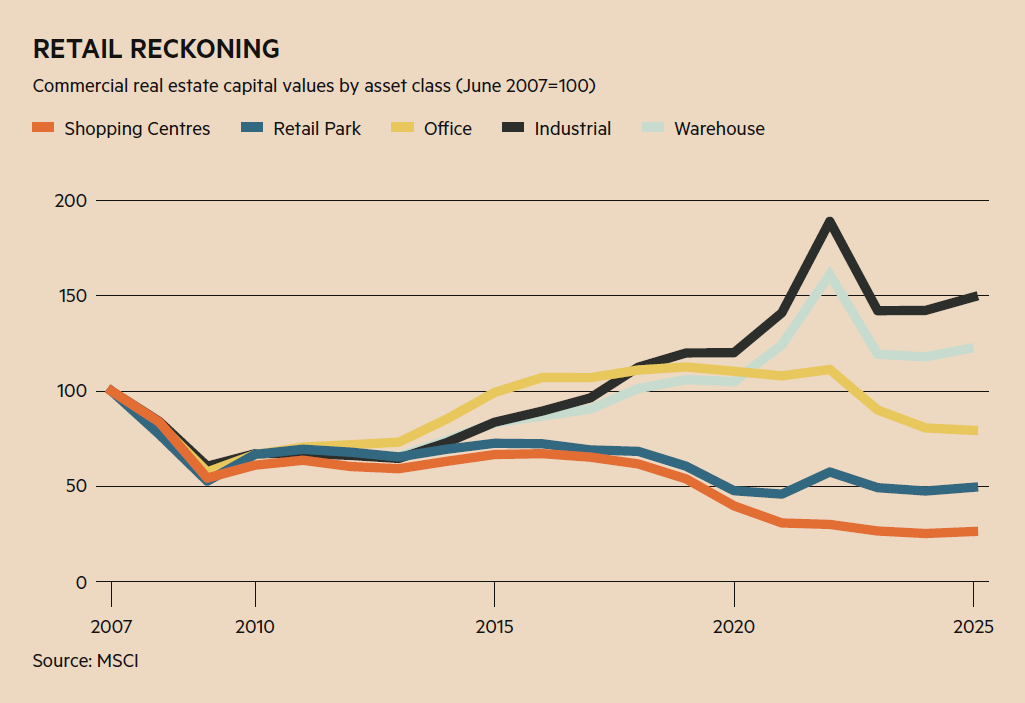

To say it has been a tricky couple of decades for retail real estate would be an understatement. The triple whammy of the financial crisis, the rise of ecommerce and the pandemic have caused capital values to fall by 50-75 per cent since 2007, according to data from MSCI, while retail park and shopping centre rents remain stubbornly below pre-crisis levels, even in prime locations.

And yet, retail has been some of the best performing real estate in the past 12 months, with footfall and sales holding up despite economic uncertainty. Industry insiders are increasingly optimistic. “Retail has been on an upward trajectory over the past 36 months . . . it’s now got a real positivity to it,” says Graham Barr, head of retail at CBRE.

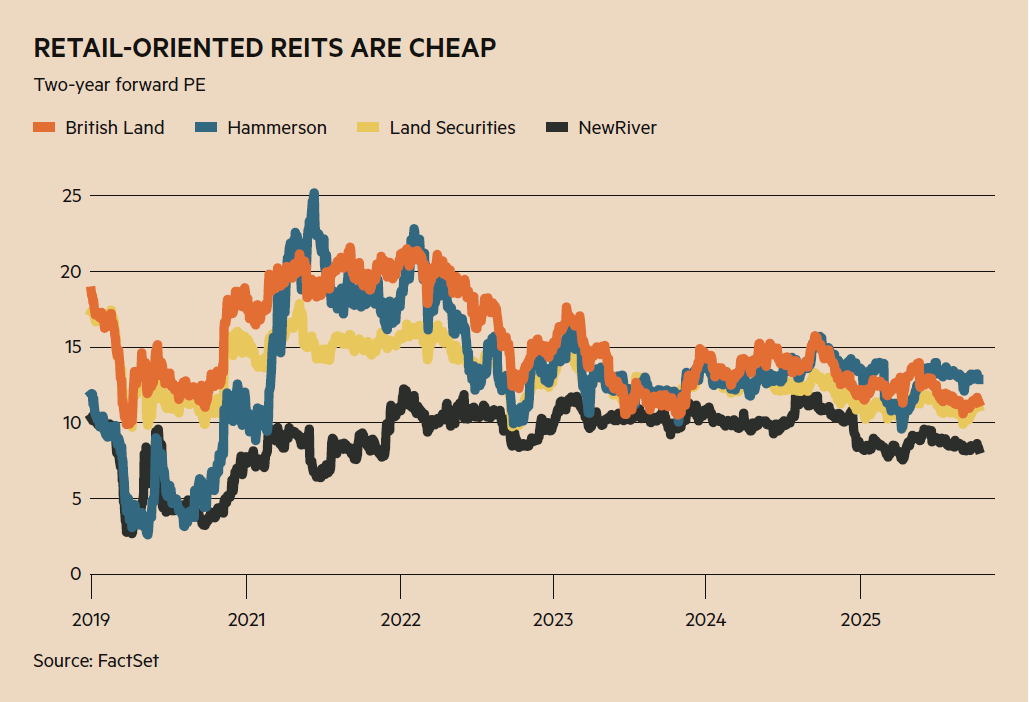

If retail truly is emerging from the bargain bin, how can investors best play it? Through shopping centres, retail parks, or the good old high street? And what risks could lie around the corner?

Technology goes from foe to friend

When it comes to eating retail real estate’s lunch, e-commerce has been the main offender. Amazon (US:AMZN) and friends accounted for an ever-growing proportion of sales through the 2010s as consumers increasingly shopped online.

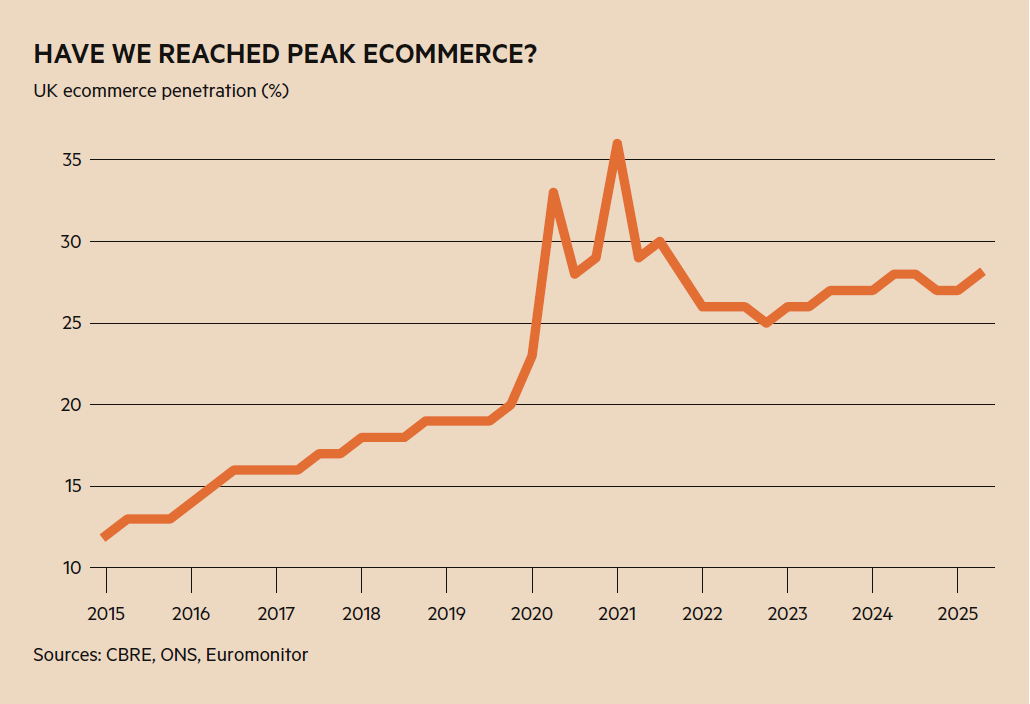

This varied by category, with consumers more comfortable buying their clothes online than their groceries. Yet ecommerce penetration has slowed since spiking during the pandemic, leading to speculation that it is peaking in the UK. “The UK has one of the highest penetrations in the world. We feel it is plateauing,” says Mark Garmon-Jones of Savills. “The disruption has taken place,” opines Bjorn Zietsman, analyst at Panmure Liberum.

Indeed, technology may now even be supportive for bricks-and-mortar retail. Omnichannel retailers (those with both a physical and an online presence) are encouraging click and collect, as well as in-person returns, ahead of costly deliveries. This not only supports margins, but also creates opportunities to cross-sell other items to shoppers during their visits. Consumers don’t mind, research from CBRE suggests, with more than half of them preferring to return an online purchase in-person.

Landlords and occupiers are also increasingly harnessing data to improve performance. The former can utilise third-party spending analysis and their own proprietary data to track customer journeys across their premises, and rearrange shop locations to optimise customer spending and occupier performance. “We offer incredible insight to our occupiers in terms of trends like footfall,” notes Josh Warren, head of investor relations at Hammerson (HMSO).

“Robust data underpins strategic decision-making across our entire business, from capital deployment to leasing, tenant mix, marketing, car park pricing and overall asset risk assessment,” says Allan Lockhart, chief executive of NewRiver Reit (NRR).

Parks and recreation

There are a number of differences between retail parks and shopping centres, the two main retail asset classes to which equity investors can gain exposure.

Retail parks are generally situated on the outskirts of towns and cities. They are highly convenient for motorists, with easy access and free parking. The sites tend to contain a few, large stores, which generally require minimal capital and operating expenditure from their owners and occupiers.

The occupiers, including grocery stores, generally have defensive business models, which make for desirable‘anchor’ tenants. Demand from more discretionary retailers has been growing recently, however, notes Barr.

Larger, easily accessible stores can have warehouse-like qualities. “Retail parks lend themselves to omnichannel retail, in a world where click-and-collect and the return to store of online purchases is so important to successful retailers’ models,” says David Walker, chief financial officer at British Land (BLND) , which has for several years been rotating into retail parks and out of offices.

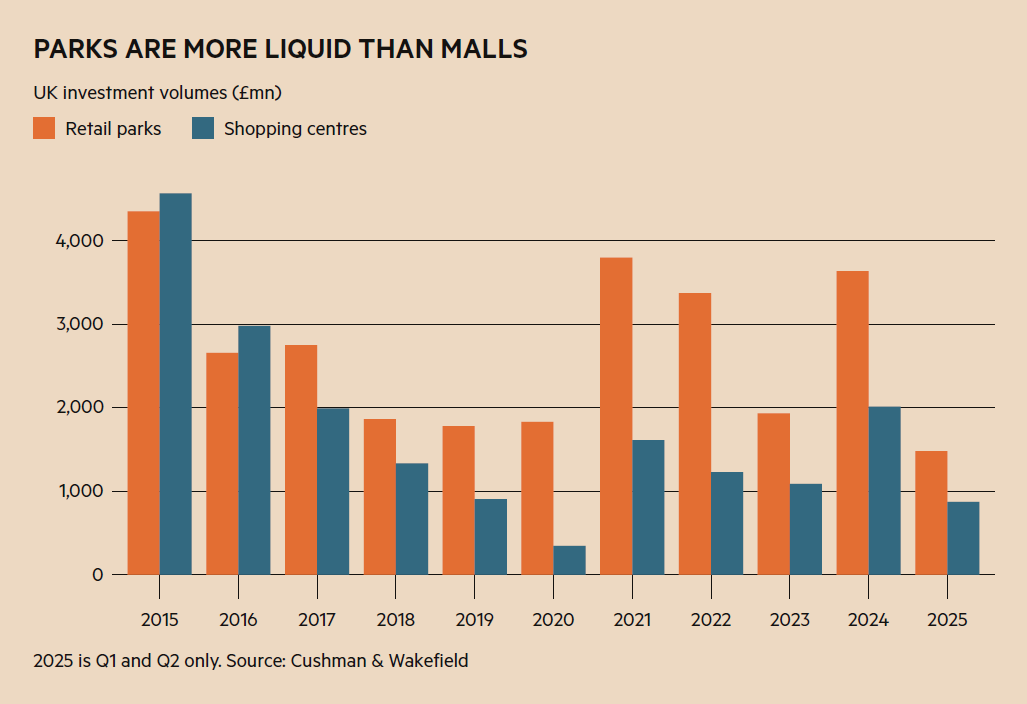

Their smaller size also makes retail parks a more liquid asset class than the likes of shopping centres or offices. “We can more easily recycle capital into the parks segment, or sell when the pricing gets to the level where this makes sense for us,” notes Walker. US behemoth Realty Income (US:O) clearly agrees, having spent £4bn on UK retail parks since 2020. This equates to a quarter of total investment volume during this period, estimates Cushman & Wakefield, a huge proportion.

Shopping centres, meanwhile, are larger sites comprising many, smaller stores, generally located in town centres, with paid parking. They are more expensive to operate than retail parks, requiring site managers, security teams and deeper levels of tenant engagement. Capex requirements are also greater.

There is also arguably more diversity within the asset class. Hammerson sees the prime location of its assets, in large urban centres, as essential to its offering to both shoppers and occupiers, which it wants to be premium brands. “The higher the quality asset and location, the more demand we have for our product,” argues Warren, who labels them “prime destinations”. The hope is that customers will travel from afar to shop, eat, drink and be merry. Land Securities (LAND) is another REIT focused on acquiring such assets as it reduces its exposure to offices.

NewRiver, on the other hand, operates what Lockhart terms “essential-led, community-focused” assets. These are more likely to have grocery stores as anchor tenants and cater to a more local customer base.

The high street has generally fared worse than shopping centres, except in the best locations, where rents and values have risen consistently. The premium valuation of Shaftesbury (SHC), which owns swaths of London’s West End, reflects this.

Looking to the future

Shopping centres’ valuations have lagged those of retail parks, as the chart above demonstrates, not least because they are more capital and operationally intensive, less liquid and more sensitive to economic cycles. However, the gap may be narrowing. “There is more mispriced value in shopping centres than retail parks,” reckons Zietsman.“Its out-of-favour status has created massive opportunities.”

Limited new supply for either asset class should support demand, and therefore price. Zietsman predicts “there probably won’t be another shopping centre built in the UK”.

More transactions – and greater price discovery – are also helping, as is the improvement in the availability and lending terms on debt. “Investors who felt illiquid, especially in shopping centres, can now see an exit for their assets,” says Marcus Wood, head of retail investment at Cushman & Wakefield. “Potential investors can also see an exit for themselves if they were to buy an asset.”

While this all sounds encouraging, risks remain. “Macroeconomics, ecommerce, occupier expansion and contraction plans, tenant failure, long-term capital investment requirements and lease profiles,” rattles off Lockhart when asked about the risks his portfolio is navigating. Retailers and their landlords will be awaiting the Autumn Budget as anxiously as the rest of us.

The potential for artificial intelligence (AI) to disrupt bricks-and-mortar retail further as ecommerce once didremains a known unknown, even if, as Edward Bavister, head of retail research at Cushman & Wakefield, notes, innovation and experience are critical among competing retailers, while new technologies such as AI are by nomeans limited to digital markets and will serve to accelerate innovation and optimise physical stores across the sector.

Future generations, including Generation Alpha, may also want a different shopping experience to older generations, threatening the status of shopping centres, in particular, as “critical social infrastructure”. Investors must shop around with both eyes open.